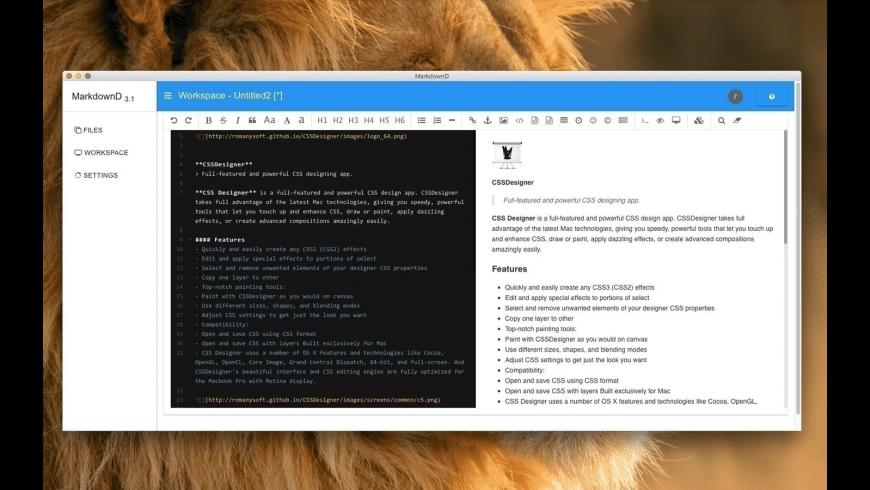

Markdown is a plain text formatting syntax for writers. It allows you to quickly write structured content for the web, and have it seamlessly converted to clean, structured HTML. It allows you to quickly write structured content for the web, and have it seamlessly converted to clean, structured HTML. Markdown is a way to write content for the web. It’s written in what people like to call “plaintext”, which is exactly the sort of text you’re used to writing and seeing. Plaintext is just the regular alphabet, with a few familiar symbols, like asterisks (. ) and backticks ( ` ). Dec 07, 2020 Markdown is a simple syntax that formats text as headers, lists, boldface, and so on. This markup language is popular, and you definitely have apps that support it. Here’s a quick primer on what Markdown is, and how and where you can use it.

-->This article provides an alphabetical reference for writing Markdown for docs.microsoft.com (Docs).

Markdown is a lightweight markup language with plain text formatting syntax. Docs supports CommonMark compliant Markdown parsed through the Markdig parsing engine. Docs also supports custom Markdown extensions that provide richer content on the Docs site.

You can use any text editor to write Markdown, but we recommend Visual Studio Code with the Docs Authoring Pack. The Docs Authoring Pack provides editing tools and preview functionality that lets you see what your articles will look like when rendered on Docs.

Alerts (Note, Tip, Important, Caution, Warning)

Alerts are a Markdown extension to create block quotes that render on docs.microsoft.com with colors and icons that indicate the significance of the content. The following alert types are supported:

These alerts look like this on docs.microsoft.com:

Note

Information the user should notice even if skimming.

Tip

Optional information to help a user be more successful.

Important

Essential information required for user success.

Caution

Negative potential consequences of an action.

Warning

Dangerous certain consequences of an action.

Angle brackets

If you use angle brackets in text in your file--for example, to denote a placeholder--you need to manually encode the angle brackets. Otherwise, Markdown thinks that they're intended to be an HTML tag.

For example, encode <script name> as <script name> or <script name>.

Angle brackets don't have to be escaped in text formatted as inline code or in code blocks.

Apostrophes and quotation marks

If you copy from Word into a Markdown editor, the text might contain 'smart' (curly) apostrophes or quotation marks. These need to be encoded or changed to basic apostrophes or quotation marks. Otherwise, you end up with things like this when the file is published: It’s

Here are the encodings for the 'smart' versions of these punctuation marks:

- Left (opening) quotation mark:

“ - Right (closing) quotation mark:

” - Right (closing) single quotation mark or apostrophe:

’ - Left (opening) single quotation mark (rarely used):

‘

Blockquotes

Blockquotes are created using the > character:

The preceding example renders as follows:

This is a blockquote. It is usually rendered indented and with a different background color.

Bold and italic text

To format text as bold, enclose it in two asterisks:

To format text as italic, enclose it in a single asterisk:

To format text as both bold and italic, enclose it in three asterisks:

Code snippets

Docs Markdown supports the placement of code snippets both inline in a sentence and as a separate 'fenced' block between sentences. For more information, see How to add code to docs.

Columns

The columns Markdown extension gives Docs authors the ability to add column-based content layouts that are more flexible and powerful than basic Markdown tables, which are only suited for true tabular data. You can add up to four columns, and use the optional span attribute to merge two or more columns.

The syntax for columns is as follows:

Columns should only contain basic Markdown, including images. Headings, tables, tabs, and other complex structures shouldn't be included. A row can't have any content outside of column.

For example, the following Markdown creates one column that spans two column widths, and one standard (no span) column:

This renders as follows:

This is a 2-span column with lots of text.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Donec vestibulum mollis nuncornare commodo. Nullam ac metus imperdiet, rutrum justo vel, vulputate leo. Donecrutrum non eros eget consectetur.

Headings

Docs supports six levels of Markdown headings:

- There must be a space between the last

#and heading text. - Each Markdown file must have one and only one H1 heading.

- The H1 heading must be the first content in the file after the YML metadata block.

- H2 headings automatically appear in the right-hand navigating menu of the published file. Lower-level headings don't appear, so use H2s strategically to help readers navigate your content.

- HTML headings, such as

<h1>, aren't recommended, and in some cases will cause build warnings. - You can link to individual headings in a file via bookmark links.

HTML

Although Markdown supports inline HTML, HTML isn't recommended for publishing to Docs, and except for a limited list of values will cause build errors or warnings.

Images

The following file types are supported by default for images:

- .jpg

- .png

Standard conceptual images (default Markdown)

The basic Markdown syntax to embed an image is:

Where <alt text> is a brief description of the image and <folder path> is a relative path to the image. Alternate text is required for screen readers for the visually impaired. It's also useful if there's a site bug where the image can't render.

Underscores in alt text aren't rendered properly unless you escape them by prefixing them with a backslash (_). However, don't copy file names for use as alt text. For example, instead of this:

Write this:

Standard conceptual images (Docs Markdown)

The Docs custom :::image::: extension supports standard images, complex images, and icons.

For standard images, the older Markdown syntax will still work, but the new extension is recommended because it supports more powerful functionality, such as specifying a localization scope that's different from the parent topic. Other advanced functionality, such as selecting from the shared image gallery instead of specifying a local image, will be available in the future. The new syntax is as follows:

If type='content' (the default), both source and alt-text are required.

Complex images with long descriptions

You can also use this extension to add an image with a long description that is read by screen readers but not rendered visually on the published page. Long descriptions are an accessibility requirement for complex images, such as graphs. The syntax is the following:

If type='complex', source, alt-text, a long description, and the :::image-end::: tag are all required.

Specifying loc-scope

Sometimes the localization scope for an image is different from that of the article or module that contains it. This can cause a bad global experience: for example, if a screenshot of a product is accidentally localized into a language the product isn't available in. To prevent this, you can specify the optional loc-scope attribute in images of types content and complex.

Icons

The image extension supports icons, which are decorative images and should not have alt text. The syntax for icons is:

If type='icon', only source should be specified.

Included Markdown files

Where markdown files need to be repeated in multiple articles, you can use an include file. The includes feature instructs Docs to replace the reference with the contents of the include file at build time. You can use includes in the following ways:

- Inline: Reuse a common text snippet inline with within a sentence.

- Block: Reuse an entire Markdown file as a block, nested within a section of an article.

An inline or block include file is a Markdown (.md) file. It can contain any valid Markdown. Include files are typically located in a common includes subdirectory, in the root of the repository. When the article is published, the included file is seamlessly integrated into it.

Includes syntax

Block include is on its own line:

Inline include is within a line:

Where <title> is the name of the file and <filepath> is the relative path to the file. INCLUDE must be capitalized and there must be a space before the <title>.

Here are requirements and considerations for include files:

- Use block includes for significant amounts of content--a paragraph or two, a shared procedure, or a shared section. Do not use them for anything smaller than a sentence.

- Includes won't be rendered in the GitHub rendered view of your article, because they rely on Docs extensions. They'll be rendered only after publication.

- Ensure that all the text in an include file is written in complete sentences or phrases that do not depend on preceding text or following text in the article that references the include. Ignoring this guidance creates an untranslatable string in the article.

- Don't embed include files within other include files.

- Place media files in a media folder that's specific to the include subdirectory--for instance, the

<repo>/includes/media folder. The media directory should not contain any images in its root. If the include does not have images, a corresponding media directory is not required. - As with regular articles, don't share media between include files. Use a separate file with a unique name for each include and article. Store the media file in the media folder that's associated with the include.

- Don't use an include as the only content of an article. Includes are meant to be supplemental to the content in the rest of the article.

Links

For information on syntax for links, see Use links in documentation.

Lists (Numbered, Bulleted, Checklist)

Numbered list

To create a numbered list, you can use all 1s. The numbers are rendered in ascending order as a sequential list when published. For increased source readability, you can increment your lists manually.

Don't use letters in lists, including nested lists. They don't render correctly when published to Docs. Nested lists using numbers will render as lowercase letters when published. For example:

This renders as follows:

- This is

- a parent numbered list

- and this is

- a nested numbered list

- (fin)

Bulleted list

To create a bulleted list, use - or * followed by a space at the beginning of each line:

This renders as follows:

- This is

- a parent bulleted list

- and this is

- a nested bulleted list

- All done!

Whichever syntax you use, - or *, use it consistently within an article.

Checklist

Checklists are available for use on Docs via a custom Markdown extension:

This example renders on Docs like this:

- List item 1

- List item 2

- List item 3

Use checklists at the beginning or end of an article to summarize 'What will you learn' or 'What have you learned' content. Do not add random checklists throughout your articles.

Next step action

You can use a custom extension to add a next step action button to Docs pages.

The syntax is as follows:

For example:

This renders as follows:

You can use any supported link in a next step action, including a Markdown link to another web page. In most cases, the next action link will be a relative link to another file in the same docset.

Non-localized strings

You can use the custom no-loc Markdown extension to identify strings of content that you would like the localization process to ignore.

All strings called out will be case-sensitive; that is, the string must match exactly to be ignored for localization.

To mark an individual string as non-localizable, use this syntax:

For example, in the following, only the single instance of Document will be ignored during the localization process:

Note

Use to escape special characters:

You can also use metadata in the YAML header to mark all instances of a string within the current Markdown file as non-localizable:

Note

The no-loc metadata is not supported as global metadata in docfx.json file. The localization pipeline doesn't read the docfx.json file, so the no-loc metadata must be added into each individual source file.

In the following example, both in the metadata title and the Markdown header the word Document will be ignored during the localization process.

In the metadata description and the Markdown main content the word document is localized, because it does not start with a capital D.

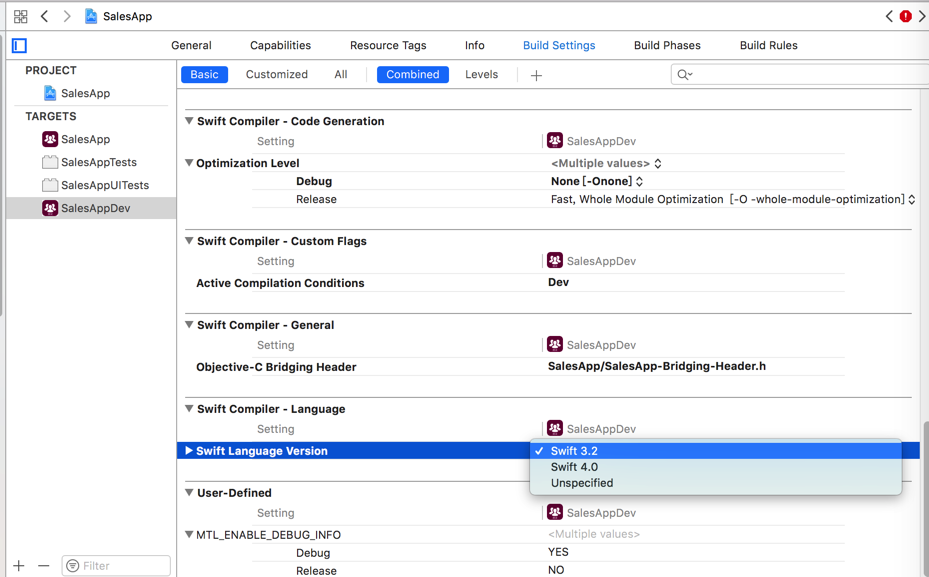

Selectors

Selectors are UI elements that let the user switch between multiple flavors of the same article. They are used in some doc sets to address differences in implementation across technologies or platforms. Selectors are typically most applicable to our mobile platform content for developers.

Because the same selector Markdown goes in each article file that uses the selector, we recommend placing the selector for your article in an include file. Then you can reference that include file in all your article files that use the same selector.

There are two types of selectors: a single selector and a multi-selector.

Single selector

... will be rendered like this:

Multi-selector

... will be rendered like this:

Subscript and superscript

You should only use subscript or superscript when necessary for technical accuracy, such as when writing about mathematical formulas. Don't use them for non-standard styles, such as footnotes.

For both subscript and superscript, use HTML:

This renders as follows:

Hello This is subscript!

This renders as follows:

Goodbye This is superscript!

Tables

The simplest way to create a table in Markdown is to use pipes and lines. To create a standard table with a header, follow the first line with dashed line:

This renders as follows:

| This is | a simple | table header |

|---|---|---|

| table | data | here |

| it doesn't | actually | have to line up nicely! |

You can align the columns by using colons:

Renders as follows:

| Fun | With | Tables |

|---|---|---|

| left-aligned column | right-aligned column | centered column |

| $100 | $100 | $100 |

| $10 | $10 | $10 |

| $1 | $1 | $1 |

Tip

The Docs Authoring Extension for VS Code makes it easy to add basic Markdown tables!

You can also use an online table generator.

Line breaks within words in any table cell

Long words in a Markdown table might make the table expand to the right navigation and become unreadable. You can solve that by allowing Docs rendering to automatically insert line breaks within words when needed. Just wrap up the table with the custom class [!div].

Here is a Markdown sample of a table with three rows that will be wrapped by a div with the class name mx-tdBreakAll.

It will be rendered like this:

| Name | Syntax | Mandatory for silent installation? | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quiet | /quiet | Yes | Runs the installer, displaying no UI and no prompts. |

| NoRestart | /norestart | No | Suppresses any attempts to restart. By default, the UI will prompt before restart. |

| Help | /help | No | Provides help and quick reference. Displays the correct use of the setup command, including a list of all options and behaviors. |

Line breaks within words in second column table cells

You might want line breaks to be automatically inserted within words only in the second column of a table. To limit the breaks to the second column, apply the class mx-tdCol2BreakAll by using the div wrapper syntax as shown earlier.

Data matrix tables

A data matrix table has both a header and a weighted first column, creating a matrix with an empty cell in the top left. Docs has custom Markdown for data matrix tables:

Markdownlint

Every entry in the first column must be styled as bold (**bold**); otherwise the tables won't be accessible for screen readers or valid for Docs.

HTML Tables

HTML tables aren't recommended for docs.microsoft.com. They aren't human readable in the source - which is a key principle of Markdown.

Note: This book has been published by Chapman & Hall/CRC. The online version of this book is free to read here (thanks to Chapman & Hall/CRC), and licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

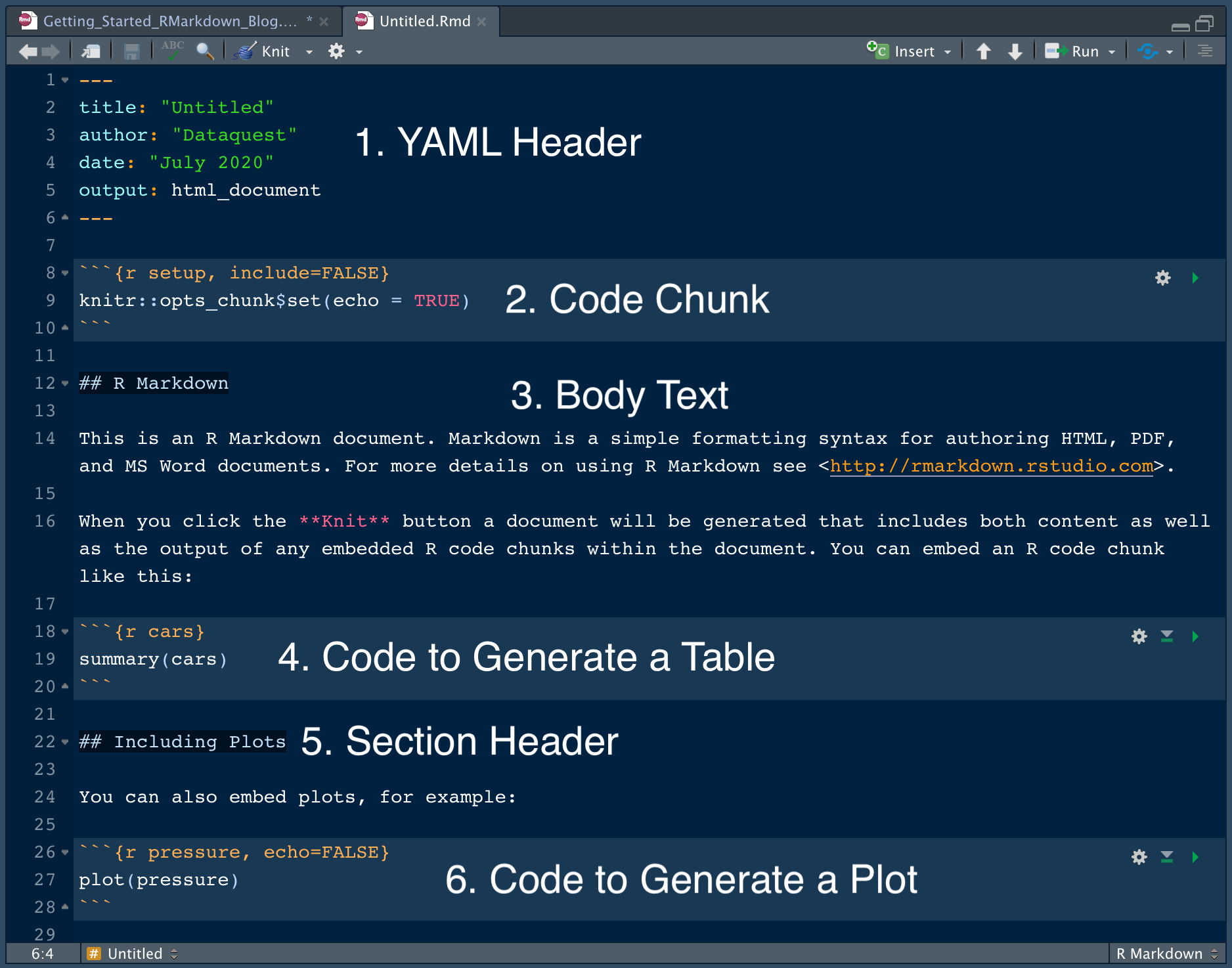

The document format “R Markdown” was first introduced in the knitr package (Xie 2015, 2021b) in early 2012. The idea was to embed code chunks (of R or other languages) in Markdown documents. In fact, knitr supported several authoring languages from the beginning in addition to Markdown, including LaTeX, HTML, AsciiDoc, reStructuredText, and Textile. Looking back over the five years, it seems to be fair to say that Markdown has become the most popular document format, which is what we expected. The simplicity of Markdown clearly stands out among these document formats.

However, the original version of Markdown invented by John Gruber was often found overly simple and not suitable to write highly technical documents. For example, there was no syntax for tables, footnotes, math expressions, or citations. Fortunately, John MacFarlane created a wonderful package named Pandoc (http://pandoc.org) to convert Markdown documents (and many other types of documents) to a large variety of output formats. More importantly, the Markdown syntax was significantly enriched. Now we can write more types of elements with Markdown while still enjoying its simplicity.

In a nutshell, R Markdown stands on the shoulders of knitr and Pandoc. The former executes the computer code embedded in Markdown, and converts R Markdown to Markdown. The latter renders Markdown to the output format you want (such as PDF, HTML, Word, and so on).

The rmarkdown package (Allaire, Xie, McPherson, et al. 2021) was first created in early 2014. During the past four years, it has steadily evolved into a relatively complete ecosystem for authoring documents, so it is a good time for us to provide a definitive guide to this ecosystem now. At this point, there are a large number of tasks that you could do with R Markdown:

Markdownlint

Compile a single R Markdown document to a report in different formats, such as PDF, HTML, or Word.

Create notebooks in which you can directly run code chunks interactively.

Make slides for presentations (HTML5, LaTeX Beamer, or PowerPoint).

Produce dashboards with flexible, interactive, and attractive layouts.

Build interactive applications based on Shiny.

Write journal articles.

Author books of multiple chapters.

Generate websites and blogs.

There is a fundamental assumption underneath R Markdown that users should be aware of: we assume it suffices that only a limited number of features are supported in Markdown. By “features,” we mean the types of elements you can create with native Markdown. The limitation is a great feature, not a bug. R Markdown may not be the right format for you if you find these elements not enough for your writing: paragraphs, (section) headers, block quotations, code blocks, (numbered and unnumbered) lists, horizontal rules, tables, inline formatting (emphasis, strikeout, superscripts, subscripts, verbatim, and small caps text), LaTeX math expressions, equations, links, images, footnotes, citations, theorems, proofs, and examples. We believe this list of elements suffice for most technical and non-technical documents. It may not be impossible to support other types of elements in R Markdown, but you may start to lose the simplicity of Markdown if you wish to go that far.

Epictetus once said, “Wealth consists not in having great possessions, but in having few wants.” The spirit is also reflected in Markdown. If you can control your preoccupation with pursuing typesetting features, you should be much more efficient in writing the content and can become a prolific author. It is entirely possible to succeed with simplicity. Jung Jae-sung was a legendary badminton player with a remarkably simple playing style: he did not look like a talented player and was very short compared to other players, so most of the time you would just see him jump three feet off the ground and smash like thunder over and over again in the back court until he beats his opponents.

Please do not underestimate the customizability of R Markdown because of the simplicity of its syntax. In particular, Pandoc templates can be surprisingly powerful, as long as you understand the underlying technologies such as LaTeX and CSS, and are willing to invest time in the appearance of your output documents (reports, books, presentations, and/or websites). As one example, you may check out the PDF report of the 2017 Employer Health Benefits Survey. It looks fairly sophisticated, but was actually produced via bookdown(Xie 2016), which is an R Markdown extension. A custom LaTeX template and a lot of LaTeX tricks were used to generate this report. Not surprisingly, this very book that you are reading right now was also written in R Markdown, and its full source is publicly available in the GitHub repository https://github.com/rstudio/rmarkdown-book.

R Markdown documents are often portable in the sense that they can be compiled to multiple types of output formats. Again, this is mainly due to the simplified syntax of the authoring language, Markdown. The simpler the elements in your document are, the more likely that the document can be converted to different formats. Similarly, if you heavily tailor R Markdown to a specific output format (e.g., LaTeX), you are likely to lose the portability, because not all features in one format work in another format.

Last but not least, your computing results will be more likely to be reproducible if you use R Markdown (or other knitr-based source documents), compared to the manual cut-and-paste approach. This is because the results are dynamically generated from computer source code. If anything goes wrong or needs to be updated, you can simply fix or update the source code, compile the document again, and the results will be automatically updated. You can enjoy reproducibility and convenience at the same time.